BY NAZARENO ALMIRÓN

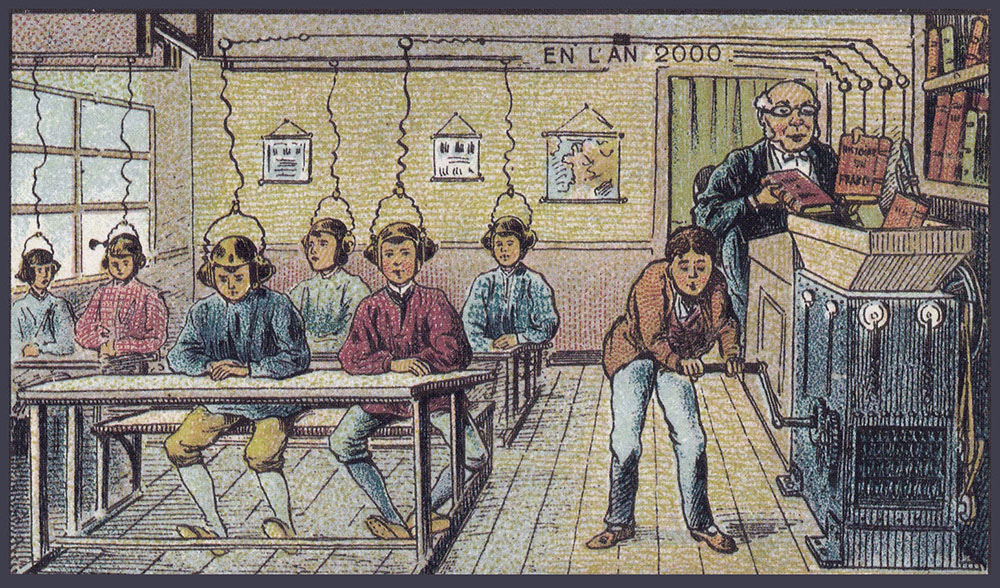

In the July 1957 issue of the American magazine Astounding Science Fiction, a short story by Isaac Asimov entitled “Profession” was presented. In it, the prolific author presented a society in which education is obtained almost instantaneously through a technology called “taping,” which is very similar to the technology seen in the movie The Matrix — “I know Kung Fu.” As with much of the genre, Asimov used the extreme situation to focus on the current state of education: the increasing dependence on technology — true in 1957 and even more so in 2020 — the relationship between knowledge and intelligence, and the space the system gives to inventiveness, creativity, and questioning.

Contents

In Profession, the protagonist finds himself at the age of 18 being rejected from the taping process, which is devastating for him since he had hoped to become a computer programmer, and to that end he had been reading about the subject to prepare his brain and somehow mold it in that direction. Later he would end up learning that this eagerness to learn with traditional methods was just one of several signs that would give away his creative capacity, necessary to generate new knowledge -that which the rest of us mortals would end up learning by tapping-. The author’s original intention always revolved around scientific knowledge, after all he himself was a man of science; but in this case we will use his work to analyze the role of the graphic designer and his training.

What is being a graphic designer?

Let’s start by asking ourselves what it means to be a graphic designer, for which I would like in this case to avoid the dictionary, and instead approach the analysis from the professional practice.

When a certain client entrusts us with a task, it can be divided into different subtasks, among which we can mention: analysis of the context of the order, research on the subject matter, research on the target audience, research on the context where the piece will be executed, technical considerations to be taken into account, analysis and arrangement of the initial material, thinking and defining the possible ways of approaching the task, generation of new material, sketching, execution of the design, preparation of the original, follow-up of the reproduction stage. The list can go on and on, depending on the task at hand. We could even add a few more subtasks, such as fee collection, or is the designer not supposed to touch money?

Now, of all these tasks -or others that have been left out of the list-, which ones could be said to correspond intrinsically to the role of designer? could we draw a line dividing those in which we are effectively executing the act of design from those that could correspond to another type of role?

Now, of all these tasks -or others that have been left out of the list-, which ones could be said to correspond intrinsically to the role of designer? could we draw a line dividing those in which we are actually performing the act of design from those that could correspond to another type of role?

As you can guess, it all depends on the scale of the resources the designer has -or is in: a freelancer will probably have to get his hands in the mud and take care of all the tasks, but it is easy to guess that just because he is a designer, not everything he does is design.

Let’s start adding some support people: a secretary can take care of your schedule, clients, consultations, etc. The role of accounts can also be of great help, and so can an administrative person for money management. So far I think we can all agree, but what would happen if the graphic designer does not know how or cannot at this moment make illustrations for this project, so he relegates this task to an illustrator? Well, the word says it, that person is dedicated to illustrate, we see no conflict here either, right? What if our designer only goes as far as making a quick sketch on a sheet of paper, and then delegates the rest of the execution of the piece to a subordinate? In that case, who designed it?

I think it is not necessary to continue with this game, we can move on to the next level: in our day-to-day work as graphic designers, we perform many tasks that -isolated- cannot necessarily be considered as part of the act of designing. If we are part of a work team, it is possible that during a given project we only perform technical or trade tasks, but that does not mean that we have stopped being designers: our training has molded us with different skills that allow us to face different tasks in a particular way, and we will always find a place to apply our knowledge. We are graphic designers not only when we are actually designing in a professional environment, but also when we do home tasks, when we watch TV or a movie, when we consume all kinds of products… Not everything we do is designing, but everything we do is as designers, inevitably.

Project thinking

This brings us to a first crossover between graphic design and Asimov’s tale: in Profession, people who learned by the tapping process cannot learn by other methods, and an update in their field necessarily requires a new tapping session in order to be up to date. If we can agree that the design process can be largely isolated from its technical execution, it is safe to say then that the training of a graphic designer must necessarily be centered on the mental processes involved in solving a graphic communication problem, and any appeal to technical issues is necessary insofar as project thinking implies practice for learning. This notion is a double-edged sword, since on the one hand the correct learning of different techniques strongly broadens our field of action as designers, improving in turn the design processes, since the greater the technical understanding, the greater the communicational effectiveness; if the training neglects technical aspects too much, professionals will have to look for other ways to learn them, at the risk of being relegated in the labor market.

In the universe proposed by Asimov, a person who does not resort to tapping every time there is an update in his field of knowledge is necessarily relegated: he will have to work for less developed regions, or he will be directly isolated from the labor market, being declared obsolete. Can this happen to a designer? It would be naive to think not, since the market will always require us to be up to date with technical issues, in fact in most cases it is the only thing that is required of us; but if we are clear that the essence of the graphic designer is to solve graphic communication problems, then we can rest assured regardless of the piece we have to design. As proof of this, it is enough to analyze the evolution of the profession in the last decades, the passage from paper to screen, from static design to animated and interactive design. By way of example, the issues of legibility, contrast and spatiality that must be taken into account when thinking about a signage project are analogous to the implications of a graphics project for virtual reality or augmented reality. The graphic resolution of an article for a magazine has clear differences whether it is a paper or web version, but the organization of the different textual typologies in levels, their distribution in the reading flow, rhythm and tone, will be issues they will have in common. Many of the pieces we design today have great similarities with those of yesteryear, and even if a completely new medium were to emerge, we should be able to analyze its characteristics, and adapt our way of working to its limitations. As a footnote, let me tell you that in any case no medium is absolutely new, otherwise it would be immediately rejected by consumers, so we can always carry out this exercise of translating the essential issues.

In short, a good graphic designer is one who is fully aware of both his capabilities and his field of action, and is never daunted by the type of piece he has in front of him. But there is a problem, and this is where we return once again to Asimov’s tale: as I said before, the author’s position revolves mainly around scientific knowledge, and the fact is that both yesterday and today, being a scientist commands admiration and respect, both for his responsibilities and for the cloak of mystery that lies behind complex knowledge. But what about the designer? I hope this question has not provoked any sardonic grimace in the reader. Well, the designer generally goes unnoticed. It is not enough for the designer to be aware of design; the market in which he or she operates must also be aware of it. We cannot perform our tasks properly if they do not give us the necessary power and freedom to do so. As I mentioned before, it is the market itself that limits the role of the graphic designer, reducing him to a bag of technical knowledge. This is clearly seen when reading job searches, where the initial focus is on the amount and type of tools we can use. In a second instance, the focus is on the visual quality of the work, which is undeniably important, but rarely is there any mention of the ability to solve problems, planning, creativity, in short, the ability to communicate and communicate.

In my experience I have had to live extreme situations from which it makes no sense to draw general conclusions. I could mention meetings to carry out desing thinking where designers were not invited, or that people with no design training impose their will by force of their position of power in the company. Leaving aside the crudest examples, this type of situation also occurs when we relate to clients, where again there is a power struggle, in extreme cases turning designers into mere technical executors of their ideas, which of course goes against the very definition of a designer. At the other extreme, we can find designers who try to monopolize everything and more, and I think it is important to mention this since it is not the intention of this text to reach that conclusion.

As designers, we have the great advantage of exercising a profession where creativity is a constant, but we also have to assume responsible roles to take care of it. On the one hand, we have the obligation to keep ourselves updated, without ever believing that the designer’s training ends when we pass the last subject; we must also play the role of communicators of our value in the market, and thus help to increase the perception that society has of us.